By Reshma Santhakumari Isman, Student, Master of Education and Alana Hoare, Assistant Teaching Professor, School of Education

It started as a conversation in a Philosophy and History of Education course among Master of Education students about community-centred teaching and how an aspiration to create more relevant learning environments was hampered by the realities of the system (e.g., time constraints, space limitations, mass education, grades over outcomes, content-driven curriculum). The bubbling hope to be better teachers persisted and we regularly returned to the concept of community-centred teaching during the semester, adding more aspirations, inspirations, and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison between teacher-, student, and community- centred teaching paradigms

| Teacher-centred | Student-centred | Community-centred |

|

|

|

Note: Adapted from A. Hoare EDUC 5020 Philosophy and History of Education, Lecture (2024, Winter).

A commitment to excellence in teaching and research hinges on a university’s ability to create and disseminate knowledge and for that knowledge to have a positive impact on the surrounding community. Community-engaged learning has gained significant attention in recent years, as universities aim to adapt research and service activities to meet the needs of community – with a focus on ‘research as service’ and collaborative efforts between groups linked to the university by location, interests, or similar circumstances to tackle issues impacting their well-being (Bidandi et al., 2021). Research suggests that community-university partnerships can be facilitated by enhancing knowledge mobilization activities, such as seminars, workshops, and conferences (Jackson et al., 2022).

Drawing on her combined experience as an international student in Canada and as a professor and student of engineering in India, Reshma had an idea about how to bring students and community together to tackle real-world problems. She reached out to Alana to see if she would consider supervising her master’s research project, which Reshma believed (and Alana agreed) had the potential to realize community-centred teaching through university-community knowledge mobilization activities. Reshma envisioned a conference designed for students and community to connect over shared dilemmas. During their conversations, Reshma and Alana wondered: How might knowledge mobilization activities help to connect community members with graduate students? Can graduate student conferences be leveraged to strengthen student-community partnerships and facilitate connections between students’ research pursuits and community needs?

Reshma has witnessed that fewer opportunities exist for international students in Canada to engage with community or to disseminate their research. International students experience various barriers that fall under the umbrella problem of not “fitting in” (Nguyen & Sharma, 2024). International students have lower capital, mobility, and power in comparison to their domestic peers due to systemic barriers within the educational system and labour market, which often includes lower levels of cultural, linguistic, resource, social, and symbolic capital (Bourdieu, 2001; Pham et al., 2019; Tomlinson, 2017). International students struggle to participate in national conferences and competitions, secure grants and scholarships, and find employment opportunities, which limits their ability to share their research and contribute to the needs of the local community.

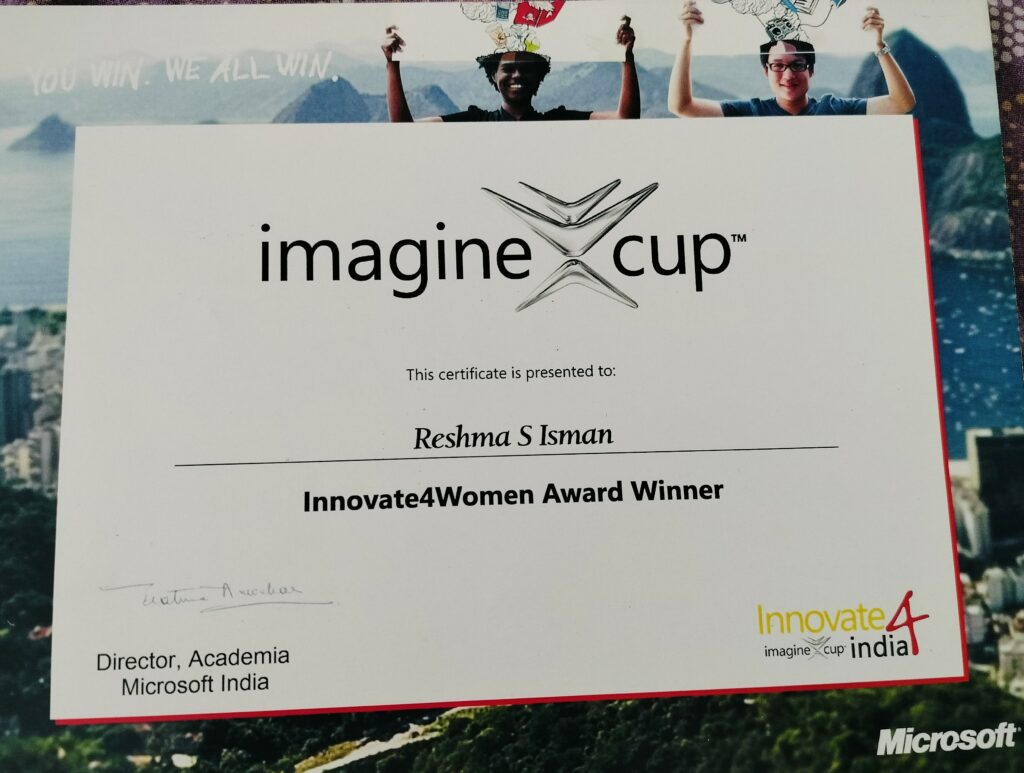

While pursuing her Master’s in Embedded Systems at the National Institute of Electronics and Information Technology, in Calicut, India, Reshma became aware of the power of combining community-engaged learning and student knowledge mobilization activities. Reshma’s university hosted the Product Design Conference – a place for industry, community, students, and faculty to gather and envision and pilot products to address local issues. Along with three classmates, Reshma presented “What Women Want (WWW)” – a product designed to protect women. Her project was selected for the Imagine Cup 2010 contest in Bangalore, hosted by Microsoft, and was recognized as the best design!

Extant research suggests that community-university conferences have the potential to bridge the divide between the academy and community. Conferences provide graduate students the opportunity to share their master’s project or thesis research with community and industry partners. The purpose of such a conference is for students to generate innovative ideas, present their ideas to community and industry partners, make connections beyond the university, and receive valuable feedback to enhance the impact of their work. The hoped-for outcome is to enhance student engagement with community, improve students’ employment opportunities, and foster research projects that address the current issues and priorities of the local community.

Community-engaged learning benefits students and the community through reciprocal exchanges of resources and knowledge. It has helped increase students’ social responsibility, openness to diversity, understanding of course content, and employment opportunities (Bidandi et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2022). By linking theory with practice and classrooms with communities, community-engaged learning can offer real-world exposure and engagement with meaningful local and global issues through concrete, hands-on practices (Hou, 2014).

Call to Action

As we embark on this research project, we seek to break down barriers between the academy and local community, particularly for international students, to make research more accessible as we strive to engage students and community as co-creators of solutions to local problems. If you’re interested in learning more about Reshma’s research and facilitating graduate student knowledge mobilization efforts, please reach out to us. You can reach Alana at ahoare@tru.ca

References

Bidandi, F., Ambe, A. N., & Mukong, C. H. (2021). Insights and current debates on community engagement in higher education institutions: Perspectives on the University of the Western Cape. Sage Open, 11(2).

Bourdieu, P. (2001). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.). Handbook for theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood Press.

Hou, S. I. (2014). Integrating problem-based learning with community-engaged learning in teaching program development and implementation. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 2(1), 1–9.

Jackson, D., & Tomlinson, M. (2022). The relative importance of work experience, extra- curricular and university-based activities on student employability. Higher Education Research and Development, 41(4), 1119–1135.

Nguyen, T. & Sharma, M. (2024, June 16). Calling for equitable access to Canadian labour market: Exploring the challenges of international graduate students in Canada [conference presentation]. Canadian Association for Social Justice Education (CASJE), Montréal, QC.

Pham, T., Tomlinson, M., & Thompson, C. (2019). Forms of capital and agency as mediations in negotiating employability of international graduate migrants. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 17(3), 394-405.

Tomlinson, M. (2017). Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Education+ Training, 59(4), 338-352.