By Lindsey McKay, Assistant Teaching Professor, Sociology

Debates are well-known as live events full of strong arguments, heated controversy, nerves, and lively theatrics. They are a great way to achieve the critical thinking and investigation institutional learning outcome. In the 2020 pivot to an online mode of delivery, the successful team debates I held in my second year Medical Sociology course looked doomed. The standard individual essay would have to replace the interaction and critical thinking learned through debates. Before I jettisoned this effective learning activity, I reached out to TRU’s instructional designers. That is when everything changed.

When I met Instructional Designer Marie Bartlett, I recall her metaphorically rubbing her hands together, saying, “hmmm, I love figuring out these learning puzzles.” Several joint sessions later, after investing what felt like weeks improving my Moodle skills, out came a multi-stage, concurrent, asynchronous debate activity-assessment in Moodle!

What does it look like?

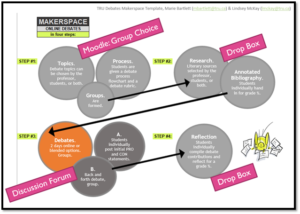

The online debate activity-assessment has four stages.

Step 1: Students form groups with 6-7 members; each group addresses a unique debate topic expressed as a proposition statement.

Step 2: Students research their debate topic. This is a graded assessment. (I use annotated bibliographies.)

Step 3: The debate! All debates start and end over the same two-day period in a discussion forum. It is asynchronous with a deadline for the first post and at least five back-and-forth posts responding to group members. All students must cite evidence (with permalinks to TRU library articles) and write a ‘pro’ and ‘con’ argument in a long first post in response to their proposition statement.

Step 4: Final graded product (final position and reflection on what they learned)

The following pictograph, created by Marie for the Makerspace event we hosted in May, illustrates the steps, and adds the Moodle resources and tools:

How did it go?

Students liked this learning activity-assessment. Many remarked in their reflections that they had to stretch their way of thinking to write a ‘pro’ or ‘con’ argument, counter to their real position. Reading the research and responding to others’ points was appreciated. Anonymous feedback included the following comments.

- “I liked how I was able to engage and interact with my peers. This was a very useful tool for honing in on our research skills. It is also great for critical thinking and challenging ourselves to view a problem from two different angles.”

- “The debate is a great idea. I loved it but I think that it was a bit confusing too to understand how it was going to be made. Having to post in both sides (pro and cons) was hard and interesting but confusing to be able to think in both arguments.”

- “I liked how we were able to have time to thoughtfully and respectfully respond to our peers with scholarly evidence without any pressure. I also liked being able to read back what others argued back with, being able to access their sources later to continue my own learning on the topic.”

- “It really challenged me to consider all points relevant and ensure sufficient evidence to support me and to include alternative approaches.”

What I learned

In F20, I learned that it was challenging for many students to do teamwork online. I resolved this by switching to individual grading; replacing the word “team” with “group.”

In W21, I learned not to go too far in minimizing reliance on one another aspect of the activity. The two-day event is very exciting as students, organized into six different groups, start to post and engage with one-another. The flurry of posts create an exciting momentum. This worked really well for five groups but one group flopped. De-emphasizing group interaction was to blame. Next time, I will impose stricter posting requirements and ensure students know their group is counting on them.

What is neat about working online is the role the software plays in shaping the design of a learning activity. One Moodle feature key to the debates was using a discussion forum type called “QandA.” I posted a ‘question,’ in this case inviting responses to the proposition statements, and the students ‘answered’ by posting their first long arguments. Only after posting can students see other students’ posts. This means no one can lean on or be influenced by the work of other students.

From Online to Blended

Now facing the return to campus, how do I pivot back? My plan is to retain the online portion and add an in-class final round of debate. Groups will debate sequentially instead of concurrently. By blending online with face-to-face modes, I will not lose the greatest strength of the online debate: citing evidence! It is far more difficult for students to clearly articulate and share scholarship supporting their arguments with the speed and time constraints of a live debate.

Each mode supports different skills sets for learners. In addition to citing scholarship, online is a slower pace that allows for deep thinking and develops writing skills. In-person requires learners to be even more prepared, think on their feet and develops oral skills. A blending should be the best of both worlds.

Interested in creating or comparing how you do debates in your course? I’d love to hear from you. Please contact me at lmckay@tru.ca. You can also download a debate OER Marie and I made from the CRICKET.trubox site, and, by request, import what I created directly into your Moodle shell.

Leave a Reply